Lester W Grau and Charles K Bartles

Introduction

Success in modern conventional warfare is determined by a combination of effort, environment and – to an extent – luck. However, the most important determinants of victory are the actions of combined arms units. Only these units, in cooperation with other branches of arms and other military services, can perform the full spectrum of defensive and offensive tasks. The execution of these tasks depends upon the enemy’s composition, position and probable course of action; the position and condition of one’s own subordinate, attached and supporting units; the conditions of the area on which the assigned tasks will occur; and weather. Traditionally, Russia’s lowest echelons capable of performing combined arms tasks were the regiment or brigade, but experimentation in the 1980s led to a semi-permanent combined arms formation at the battalion level, the Battalion Tactical Group (BTG).

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has made the term ‘Battalion Tactical Group’ commonplace beyond the expert community, from the mass media to YouTube and a plethora of blog sites. Though understanding of the invasion is still in its infancy, this article intends to shed some light on what a BTG is, and how it is used in a Russian military context.

At the time of writing, details are still sketchy, but based upon media reports and a few captured Russian maps, it appears that Russia has conducted a partial mobilisation, deploying only partial divisions/regiments, brigades, and independent BTGs. Larger formations have apparently deployed only with their BTGs, leaving their other manoeuvre battalions in garrisons. Although the Russians appear to be having difficulties, this structural change was likely envisioned from the beginning of the operation, as the scale of the conflict is unsuitable for the sole use of independent BTGs. The BTG was ideal for earlier fighting in support of separatist ethnic Russian elements in Donetsk and Luhansk; however, large-scale combat requires large-scale combined arms operations and battalions fighting as part of larger entities.

The brigade/regiment may now be the primary unit of manoeuvre, but some independent BTGs likely remain in play. They are either being spun off a parent regiment/brigade for a particular mission (such as forward detachments, advance guards, raiding detachments, flank guards, or urban assault detachments) or may be entirely independent. It is likely that some BTGs will be subordinated to regiments/brigades that they are not otherwise affiliated with, and possibly to different branches, including the naval infantry and airborne troops (VDV), if expedient.

History of the Battalion Tactical Group

The BTG is not a new feature in Russian military thought. The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) included raiding groups, forward detachments, rear guards, advance guards and other mobile battalions comprised of horse cavalry, machinegun detachments mounted on horse-drawn carts, horse-drawn artillery, and occasional tanks or armoured cars. Their focus was on speed, manoeuvre, the ability to mass fires and forces, and the interaction of these forces to achieve a combined combat power greater than the component parts. During the Second World War, the Soviets fought primarily with separate infantry, armour and artillery units that occasionally fought as combined arms units, but usually integrated shortly before the battle. Artillery and artillerymen were always present in infantry battalions in the form of mortars, direct-fire cannon and antitank rifles.

During the Cold War, the Soviets realised that combined arms units were more effective than integrating branch units just before the fight. There were problems integrating them in garrison and training. Branch units occupied their own barracks. Tanks, personnel carriers and artillery required different maintenance parts and services. Branch weapons qualification required different ranges and facilities. Branch proficiency was necessary before putting different branch soldiers together in exercises or combat. So the Soviet Army trained for branch skills, but when it went on field exercises, it fought combined. The results were not always inspiring. Commanders struggled to integrate their branch forces with those of other branches – though units that trained together on a sustained basis performed better.

Over time, divisions and regiments became fairly proficient in combined arms combat, but the nature of the battlefield was changing. Modern weapons forced units to spread out in order to survive. The future battlefield would be fragmented, with gaps between units, open flanks and combat not only at the front line, but also throughout the battlespace. The concept of the front line itself was being challenged. It thus became obvious that the battalion was a prime component of future war and battalions had to fight combined to win. The problem was how to combine branches into battalions and fight effectively. What was the optimum mix of tanks, mounted infantry, artillery, engineers, air defence and other branches? How could they be trained simultaneously and effectively in branch and combined arms skills?

Throughout the Cold War, the Soviets tried different combinations of forces in an effort to create an optimum Combined Arms Battalion, or Battalion Tactical Group in the Russian parlance. It had to be lethal, yet not too large, capable of acting independently for a period of days, and able to fight combined effectively. From the 1960s to the end of the 1980s, the Soviet Motorised Rifle Battalion and Tank Battalion went through several Table of Organisation and Equipment (TO&E) changes to try to improve their combined arms lethality. During the same period, they conducted hundreds of exercises using different mixes of tanks, motorised rifle, air defence, engineers and combat support forces, looking for the optimum solution. Clearly, the Soviets were trying to determine the optimum TO&E structure, training and employment of BTGs.

After the collapse of the USSR, the impetus to develop the BTG was strengthened by Russia’s experience during the Chechen campaigns and related counterterrorism activities. During this period, the 58th Combined Arms Army manoeuvre regiments formed BTGs based on motorised rifle battalions that were reinforced with tanks; artillery; air defence; reconnaissance; engineering; chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defence; communications; maintenance; and logistics units. These BTGs were 100% equipped and manned, with mostly contract personnel, and were on a six-month readiness cycle until their personnel were rotated out. Many characteristics of today’s BTG can be directly traced to this time.

Battalion Tactical Groups in Today’s Russia

Today, the BTG is a semi-permanent task force found in the manoeuvre (motorised rifle and tank) regiments and brigades of the Russian Ground Forces, Naval Infantry and VDV. BTGs are task-organised motorised rifle or tank battalion-plus-sized combat entities that can perform semi-independent combined arms combat missions. They are capable of conducting deep raids, envelopments and flanking manoeuvres. In the Russian system, the lowest echelon of combined arms command has traditionally been the manoeuvre regiment or brigade. Thus, the Russians do not use terms like ‘Regimental Tactical Group’ when referring to their manoeuvre formations, as these formations are inherently combined arms in nature. The term ‘Battalion Tactical Group’ is a special delineation of function which notes that this formation is combined arms in nature.

By current Russian General Staff directive, each regiment and brigade is supposed to have two designated BTGs. But units in the Southern Military District reportedly have three BTGs per regiment/brigade. In terms of composition, a BTG consists of a motorised rifle battalion or tank battalion with varying combat support attachments. These attachments can vary, as they depend upon the equipment organic to the battalion and the tasks it is likely to be assigned. The most common BTG variant is based on a motorised rifle battalion with an attached tank company, self-propelled howitzer battalion, air defence platoon, engineer squad, and logistic support.

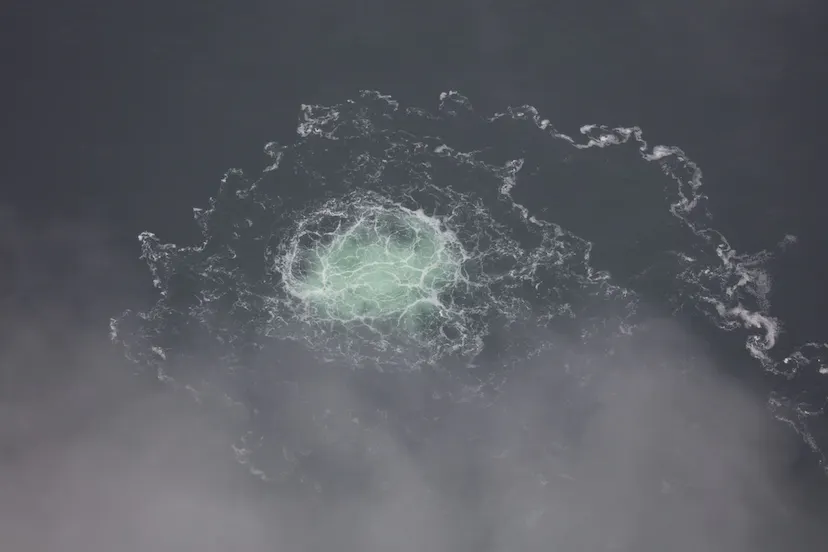

Figure 1: Example of a Battalion Tactical Group (circa 2014–2015)